Introduction to Work-Based Learning

Overview

What Is Work-Based Learning?

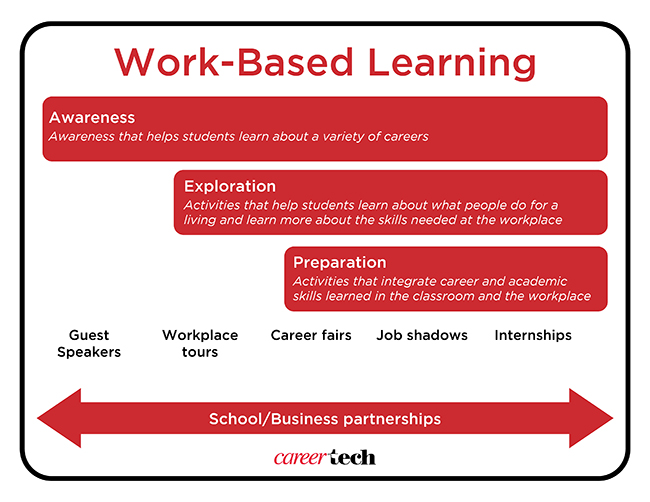

k-based learning (WBL) is a set of instructional strategies that engages employers and schools in providing learning experiences for students. WBL activities are structured opportunities for students to interact with employers or community partners either at school, at a worksite, or virtually, using technology to link students and employers in different locations.

The purposes of WBL are to:

- Build student awareness of potential careers

- Facilitate student exploration of career opportunities

- Begin student preparation for careers

These awareness, exploration, and preparation activities help students make informed decisions about high school course and program enrollment and about postsecondary education and training. Exposure to careers through an individual WBL activity can be beneficial, but students attain best results when WBL activities are structured and sequenced over several years.

WBL should be integrated with classroom learning to help students draw connections between coursework and future careers. Students need time and assistance to prepare for WBL activities as well as opportunities to reflect on the activities afterward.

Quality work-based learning should include the following elements:

- A sequence of experiences that begins with awareness and moves on to exploration and hands-on preparation.

- Clearly defined learning objectives related to classroom curricula.

- Alignment with students’ career interests.

- Alignment with content standards and industry/occupational standards.

- Exposure to a wide range of industries and occupations.

- Collaboration between employers and educators, with clearly defined roles for each.

- Activities with a range of levels of intensity and duration.

- Intentional student preparation and opportunities for reflection.

This WBL Implementation Guide has been developed by FHI360 and adapted by Oklahoma CareerTech to guide implementation of WBL activities. Before moving on to a chapter about a specific WBL activity, users should review the entire introduction. It provides information pertinent to all WBL activities, which will enable district or school staff members to implement WBL activities in a broader, well-planned context.

How to Use This Guide

The CareerTech Work-Based Learning Implementation Guide is a how-to guide with suggestions and tools for planning and implementing specific WBL activities. While district or school priorities for implementing WBL may vary, as will the variety of local employers with which to partner, the manual provides information that will help in implementing each activity in the context of the complete WBL continuum.

This Introduction provides:

- An overview of WBL activities

- Their benefits to students, schools, and employers

- The skills to be developed through WBL

- Suggestions for planning the overall WBL program

- Important steps for implementing WBL activities

- Guidance for the critical tasks of managing collaboration with the wide range of essential stakeholders, especially employers

Each of the other chapters provides more detailed information about a specific WBL activity: ideas on which stakeholders to engage; a suggested implementation time line; resource templates and tools; and links for more information. In addition, each WBL activity chapter provides ideas for student preparation as well as suggestions for employer preparation. The timelines and tools in the manual are suggested best practices that should be adapted to suit the specific needs of the participating schools and employers. For example, what works well in a larger, urban district may need to be scaled down to fit more rural communities that have fewer employers spread across greater distances.

Benefits of Work-Based Learning

Well-planned WBL programs benefit all participants in multiple ways.

Benefits to students:

- Set and pursue individual career goals based on workplace experiences.

- Engage parents in career planning.

- Get a “foot in the door” for possible future part-time, summer, or eventual full-time jobs.

- Become aware of career opportunities, explore those of interest, and start preparing for them.

- Build understanding of skills required to succeed in the workplace.

- Recognize the relevance of education to career success and increase motivation for academic success.

Benefits to schools:

- Build relationships with the community.

- Make classroom learning more relevant.

- Enable students to share their experiences with peers and teachers.

- Provide staff development opportunities.

- Increase staff understanding of the workplaces for which they are preparing students.

- Expand curricula by using workplaces as learning environments.

Benefits to employers:

- Build positive relationships with school staff and students.

- Help create a pool of better-prepared and motivated potential employees.

- Strengthen employees’ supervisory and leadership skills.

- Improve employee retention and morale.

- Learn about the knowledge and skills of today’s students and tomorrow’s employees.

- Generate favorable visibility in the community.

- Derive value from student work.

- Make contacts with potential candidates for part-time, summer, or eventual full-time jobs.

Work-Based Learning Continuum

The WBL continuum is a sequence of activities that starts with low-intensity experiences that begin to engage students in thinking about careers and gradually progresses into more in-depth, intensive experiences that include opportunities for hands-on learning. WBL also includes expanding teachers’ knowledge of the employers in their region and the careers that might be available to their students.

Career Awareness

Career awareness activities help students learn about a variety of careers, the education and training required for those careers, and the typical pathways for career entry and advancement. Career awareness activities expose students to a wide range of occupations in the private, public, and non-profit sectors.

Career awareness activities generally have the following characteristics:

- Industry or community partners provide a learning experience for students, usually in groups.

- The activity is designed and shaped by educators and employer partners to broaden students’ knowledge by introducing a wide range of careers and occupations.

- The activity provides information about the types of careers available, the people in them and what they do, and the education and training required for those careers.

- Students learn about appropriate workplace behaviors.

- Students have opportunities to reflect on what they have learned and begin to identify interests for further exploration.

- Students in the middle and high school grades may all benefit from career awareness activities, providing they are tailored to the specific grade level.

Career awareness activities might include:

- Guest speakers (Chapter 2)

- Workplace tours (Chapter 3)

- Career fairs (Chapter 4)

Career Exploration

Career exploration activities help students learn about the skills needed for specific careers by observing and interacting with employees in the workplace. As a next step after career awareness, career exploration activities are usually more focused on specific careers in which students are interested.

Career exploration activities generally have the following characteristics:

- Students interact one-on-one with employees in a specific industry or occupation.

- They are usually one-time or one-day events.

- Students play active roles in selecting and shaping the activities, based on their individual interests.

- Students have opportunities for deeper analysis and reflection to help refine their choices about future education and training.

- They are best suited to high school students.

Career exploration activities might include:

- Informational interviews (Chapter 5)

- Job shadows (Chapter 6)

Career Preparation

Career preparation activities integrate career and academic skills acquired in the classroom with skills and knowledge acquired in the workplace. The emphasis is on building employability and work readiness skills and on understanding applications of school-based learning to specific careers. Many students use these activities to help make decisions about future education and training options.

Career preparation activities generally have the following characteristics:

- They build on the interests developed in career awareness and exploration activities by providing more in-depth, hands-on experiences.

- Students interact one-on-one with employees in a specific occupation or industry over an extended period of time.

- Students engage in activities that have career development value beyond success in school.

- Both students and employers benefit from the experience.

- Student performance is evaluated by employers.

- The activities are connected to the academic and career/technical curricula.

- They are of sufficient duration and depth to enable students to develop and demonstrate specific knowledge and skills and to make further education and career planning decisions.

- They are applicable to multiple postsecondary education and career options.

- They are most suitable for high school students, typically in the 10th to 12th grades, because they help inform both short- and longer-term decisions about career choice, course selection, and planning for postsecondary education.

Apprenticeships

Youth Apprenticeship allows high school juniors and seniors to combine academic instruction and on-the-job training for elective credit. Postsecondary Apprenticeships provide on-the-job training and classroom instruction, sometimes for college credit. Registered Apprenticeship is a structured education and training program that combines on-the-job training with related classroom instruction. Apprentices are full-time, paid employees who receive instruction and mentoring from skilled workers. Apprentices are trained to the employer’s standards using the employer’s equipment and protocols. Upon completion of the program, apprentices receive a nationally recognized credential.

There are several other types of learning-by-doing career preparation activities which are not addressed in this manual. Users may wish to investigate alternatives such as school-based enterprises (e.g., student-run businesses), service learning (e.g., using volunteer projects as simulated workplaces), or cooperative education (e.g., combining part-time or alternating periods of school and work). These options are beyond the scope of this manual and offer quite similar experiences to the internships addressed in Chapter 7.

Work-Based Learning for Teachers

Students and employers are not the only ones who can benefit from WBL. Participating in WBL activities can improve teachers’, counselors’, and administrators’ capacity to guide students’ career development work by bringing actual work experiences into classrooms, counseling settings, and the larger school community. WBL for teachers, for example, can be used for curriculum development and for integrating work-related concepts and experiences into instruction.

Teacher WBL activities generally have the following characteristics:

- They expand teachers’ knowledge of the careers in which their students are interested.

- They familiarize teachers with the skills and education required for specific careers.

- They connect teachers with employers for either short-term or extended interactions in the workplace.

- They include opportunities for teachers to reflect on their experiences and determine how they will apply what they learn in their classrooms.

- Sometimes they enable participating teachers to earn continuing education or graduate credits.

Teacher WBL activities may include:

- Teacher workplace tours (Chapter 8)

- Teacher externships (Chapter 9)

Skills Developed Through Work-Based Learning

One of the purposes of WBL is to help students develop skills and behaviors that are essential to success in every workplace. The following chart presents a typology of workplace skills. It is reprinted, with permission, from A Work-Based Learning Strategy: Career Practicum by ConnectEd: The California Center for College and Careers. Many states and school districts have incorporated versions of these workplace skills into their standards for learning.

When implementing WBL activities, it is important to build in opportunities for students to develop these skills and to work with employer partners to ensure that they address them in their work with students.

| Category | Student learning Outcome |

|---|---|

| Student... | |

| Collaboration and Teamwork | Builds effective collaborative working relationships with colleagues and customers; is able to work with diverse teams, contributing appropriately to the team effort; negotiates and manages conflict; learns from and works collaboratively with individuals representing diverse cultures, ethnicities, ages, gender, religions, lifestyles, and viewpoints; and uses technology to support collaboration. |

| Communication | Comprehends verbal, written, and visual information and instructions; listens effectively; observes non-verbal communication; articulates and presents ideas and information clearly and effectively both verbally and in written form; and uses technology appropriately for communication. |

| Creativity and Innovation | Demonstrates originality and inventiveness in work; communicates new ideas to others; and integrates knowledge across different disciplines. |

| Critical Thinking and Problem Solving | Demonstrates the following critical-thinking and problem-solving skills: exercises sound reasoning and analytical thinking; makes judgments and explains perspectives based on evidence and previous findings; and uses knowledge, facts, and data to solve problems. |

| Information Management | Is open to learning and demonstrates the following information-gathering skills: seeks out and locates information; understands and organizes information; evaluates information for quality of content, validity, credibility, and relevance; and references sources of information appropriately. |

| Initiative and Self-Direction | Takes initiative and is able to work independently as needed; looks for the means to solve problems; actively seeks out new knowledge and skills; monitors his/her own learning needs; learns from his/her mistakes; and seeks information about related career options and postsecondary training. |

| Professionalism and Ethics | Manages time effectively; is punctual; takes responsibility; prioritizes tasks; brings tasks and projects to completion; demonstrates integrity and ethical behavior; and acts responsibly with others in mind. |

| Quantitative Reasoning | Uses math and quantitative reasoning to describe, analyze, and solve problems; performs basic mathematical computations quickly and accurately; and understands how to use math and/or data to develop possible solutions. |

| Technology | Selects and uses appropriate technology to accomplish tasks; applies technology skills to problem solving; uses standard technologies easily; and is able to access information quickly from reliable sources online. |

| Workplace Context and Culture | Understands the workplace’s culture, etiquette, and practices; knows how to navigate the organization; understands how to build, utilize, and maintain a professional network of relationships; and understands the role such a network plays in personal and professional success. |

How to Develop a Work-Based Learning Plan

A robust WBL program has many moving parts: scheduling multiple WBL activities for students from multiple schools; recruiting employers to participate in multiple WBL activities; coordinating with school schedules; matching up students with employers according to students’ career interests and employer expectations; managing the logistical details of WBL activity implementation; ensuring that both students and employers are well-prepared for each WBL activity, providing for post-activity reflection and evaluation; and capturing lessons learned from implementation that can be used for continuous improvement. Without a good overall plan, too many critical tasks can slip through the cracks, it is harder for school staff to integrate WBL activities into the classroom curriculum, and employers could be bombarded with multiple, fragmented – and eventually unwelcome – requests for participation in WBL activities. While the how-to description below is designed to help districts and schools of all sizes, a more abbreviated approach may be more suitable in smaller, more rural regions.

The WBL coordinator should begin by convening key stakeholders to develop a comprehensive WBL plan.

The WBL coordinator (and other district or school staff) should begin by convening key stakeholders to develop a comprehensive WBL plan that will:

- Provide a framework and context for all WBL activities.

- Engage key education and employer stakeholders to gain their support and ensure that WBL activities can be carried out efficiently and effectively.

- Lay out a schedule of which WBL activities will be implemented for which students/schools at what point in the year.

- Identify resources (human and financial) that will be needed and how they will be obtained.

- Set priorities for making the inevitable trade-offs required by resource limitations.

- Define roles and responsibilities for those involved in implementation.

- Define how WBL activities will complement classroom curricula and be integrated into academic learning.

In addition to serving as a framework for organizing the work of WBL coordinators and other district or school staff, the WBL planning process is an opportunity to enlist the support of those most critical to implementation of individual WBL activities. The plan will also define the costs associated with specific WBL activities (typically transportation to workplaces, substitute teachers, facility and food costs for career/college fairs, and staffing to provide support and supervision for activities that are implemented in the summer) with enough lead time to enable staff to develop strategies for securing the necessary budget resources. The planning process also provides a context for setting overall WBL priorities for a district or school.

There may already be a WBL plan in place. In that case, the WBL coordinator should determine how it should be updated, strengthened, or otherwise revised. If a plan is in place, staff should identify employers that have participated in WBL activities in the past and assess the nature and quality of their previous involvement. Key stakeholders should be involved in any revisions so that their support for the plan is assured. WBL coordinators may find it necessary to meet immediate demands for WBL activities concurrently with developing a more comprehensive plan.

The first step in developing a WBL plan is to recruit a committee of stakeholders to engage as partners in the planning process. The following stakeholder partners are critical:

- District and school administrators (including career and technical education [CTE] administrators)

- Major employers and employer associations (e.g., chambers of commerce)

- Relevant local, regional, and state agencies (e.g., workforce development boards, economic development agencies, and state departments of labor and/or commerce)

- Counselors

- Career advisors

- Teachers

- Postsecondary representatives (from two- and four-year colleges and universities, technology centers and other technical schools, certificate or licensure programs, and apprenticeships)

- CTE program business and industry councils

(Note: Workforce development boards (WDBs), sometimes called workforce boards or workforce investment boards (WIBs), coordinate workforce development resources at the state, regional, and/or local levels, develop strategic plans, and establish funding priorities. More than 50 percent of each WDB’s members must come from the business community. For further information, visit the National Association of Workforce Boards.)

Parents and students (and perhaps young alumni) should also be involved in the planning process, but it may make more sense to obtain their perspectives through focus groups early in the process rather than to ask them to attend a series of meetings where only parts of the discussion will be of interest.

Recruitment of employer representatives should be focused on individuals who can provide a broad range of diverse employer perspectives and can devote the necessary time. Certainly, the largest employers in the region should be asked to participate, but recruitment of employer representatives should probably focus on employer associations like chambers of commerce, other industry or trade associations (e.g., manufacturers association or home builders association) and service clubs (e.g., Rotary, Kiwanis, and Lions). These associations and clubs can provide their members’ perspectives, and they also can be valuable partners for recruiting their members to participate in WBL activities.

Representatives from local governments, regional workforce development boards, economic development agencies, non-profit organizations, and state departments of labor or commerce can also offer knowledge and expertise to the planning process. There may be smaller employers that are willing to engage in the planning process, but staff should try to limit the inconvenience of doing so; it might be easier for them to meet once (or have a telephone conversation/interview) with a staff member to provide their perspectives on the WBL plan than to attend a series of meetings.

The WBL coordinator should design the planning process in such a way that there are as few meetings as possible, and most of the work is done by staff between meetings.

The WBL coordinator should design the planning process in such a way that there are as few meetings as possible, and most of the work is done by staff between meetings. For example, a kick-off meeting might be devoted to introducing WBL objectives and activities, reviewing any previous WBL activities in the district, describing how WBL activities benefit all participants, and asking each partner to share perspectives on the value of WBL and the practical considerations the plan should address. A second meeting might be scheduled to review a staff-prepared draft plan and identify gaps or any revisions that might be needed. This draft plan could be circulated more widely to enable other stakeholders, such as principals, to comment before the plan is finalized. A third and final meeting would approve the plan and focus on how each partner can help in implementation.

The WBL coordinator should determine what will be the most useful format for a WBL plan. It may be as simple as a calendar with a weekly or monthly listing of which WBL activities are planned for which students and which employers. A more elaborate narrative document might be useful in building awareness of WBL and in recruiting employers for specific WBL activities, but it is not essential that such information be in the plan itself.

A summary of the plan should be made widely available to as many stakeholders as possible so that they know what to expect. It may also be used as a tool for engaging media interest in WBL.

How to Implement Work-Based Learning Activities

There is no single right way to implement WBL activities, and the responsibility for doing so may rest with a variety of individuals. This manual is intended to help anyone responsible for implementing a WBL program: counselors; career advisors; school administrators; teachers; or other district and school staff members. The term WBL coordinator is used throughout the manual to refer to the individual responsible for coordinating a WBL activity and serving as a single point of contact for employers. Typically, the WBL coordinator acts as a liaison between employers and educators and ensures that each aspect of the WBL activity is implemented successfully. Depending on the specific WBL activity and context, school site responsibilities may rest with counselors, career advisors, teachers, or administrators.

When introducing WBL activities to a community or region, it is wise to start with those that are easiest to implement successfully — particularly those in which employers are most likely to participate. A good strategy might be to start with WBL activities like guest speakers, workplace tours, or informational interviews that afford employers the opportunity to interact with students with minimal risk and a very modest commitment of time. Positive early experiences may lead to employer willingness to engage in WBL activities requiring a higher level of engagement, such as job shadows or internships.

The key stakeholders required for implementing WBL activities will almost always include the following:

- Employers

- District and school administrators

- Career advisors

- Counselors

- Teachers

- Students

- Parents

- Local or regional CTE staff

The following stakeholders may also be included:

- Postsecondary representatives

- Employer associations such as chambers of commerce, other industry or trade associations, service clubs, and economic development organizations

- Regional workforce development boards

- State departments of labor or commerce

Implementation of a specific WBL activity usually includes the following steps:

- Identify the stakeholders needed to assist with the specific WBL activity.

- Collect information on students’ career interests to help target employer recruitment.

- Recruit stakeholders to participate in the WBL activity. This step can take substantial time; an early start will help significantly.

- Keep all participating stakeholders informed at each stage of implementation.

- For WBL activities that take place in the summer (e.g., student internships and teacher externships), the district or school may need to budget for related staffing and logistical costs and ensure appropriate staffing throughout implementation.

- Prepare students, employers, and other participants for the WBL activity. Ensure that everyone involved understands – and accepts – his or her responsibilities.

- Carry out the WBL activity. Document it with photos, attendance lists, or other appropriate means.

- Provide structured opportunities for students to reflect on what they learned and how they can apply it to subsequent career development and academic work.

- Obtain evaluations of the WBL activity from students and employers; these should be used for continuous improvement of the WBL program.

- Extend thanks and provide recognition to participating stakeholders, especially employers.

More detailed information, including suggestions for implementation, time lines, and resource materials can be found in each WBL activity chapter.

Managing Stakeholders

When implementing WBL activities, each stakeholder needs to understand the purpose of the activity, the benefits of participating, his or her specific role, the time line for implementation, and the resources that will support implementation. This means that the WBL coordinator will need to keep track of every interaction with each stakeholder to make sure that the right information gets to the right party at the right time. Efficient tracking of stakeholder contacts and the roles and responsibilities each assumes are crucial to success. A WBL database that tracks school staff and employer contacts will prove to be a vital asset for managing WBL activities. A sample WBL database template is provided in the Resources section of this introduction.

The WBL database should be created by the district or school staff member who will be responsible for entering and managing the information; frequent and consistent updating will be required. The WBL database not only tracks specific contact information and tasks related to individual WBL activities; it can also be used to track participation of schools and employers over time. As more WBL activities are implemented and staff changes occur, new staff members can use the database to ensure consistency and continuity.

The WBL database should be designed to be accessible to the WBL coordinator and other stakeholders such as school-based staff, who may need access to carry out their responsibilities. This can be accomplished by saving the document to an intranet or by using online services or “cloud” tools.

Employer Engagement and Communication

Engaging a wide range of employers in multiple WBL activities every year is critical to the very existence of WBL programs, let alone their success. WBL coordinators have no more important task, and they probably do not have a more challenging one.

Engaging a wide range of employers in multiple WBL activities every year is critical to the very existence of WBL programs, let alone their success. WBL coordinators have no more important task, and they probably do not have a more challenging one. The more effectively coordinators engage with employers from the outset, the easier it becomes to plan and implement the full range of WBL activities.

Employer engagement should take place on at least two levels: (1) broad awareness in the community about the role of WBL in preparing students for careers and (2) recruitment of specific employers to participate in one or more WBL activities. The WBL coordinator will need to build an extensive network of employer contacts (starting with the participants in the planning process described earlier in this introduction and/or with employers that may have participated in WBL activities in the past) that can be used to plan and implement specific WBL activities. These contact networks should be managed and maintained using the WBL database described above. Communications with employers should be succinct, informative, and tailored to the recipients’ needs and organizational cultures. Whenever possible, communications should build on employers’ previous WBL involvement. Because WBL is not a one-time initiative, special efforts should be made to retain employers as WBL participants year after year.

Broad Awareness in the Community and Among Employers

General community awareness of the role of WBL in helping students set and pursue education and career goals is the foundation on which all employer engagement is built. It is much easier to engage an employer in conversation about hosting a job shadow, for example, if the conversation does not have to start with explaining what WBL is all about, why it is important for students, and how it can benefit employers.

The audiences for WBL awareness outreach are much broader than the more targeted audience for recruiting hosts for internships in a specific occupation, for example, because awareness and word of mouth are powerful recruitment tools. The WBL coordinator should think broadly about how to reach all kinds of employers, not only in the business sector but also in the public and non-profit sectors and among the self-employed. There are many ways to reach employer audiences, both directly and indirectly, with general information about WBL that can pave the way for successful recruitment of employers to participate in specific WBL activities. Some useful ways to build awareness include:

- Contact employer associations such as chambers of commerce, other industry or trade associations, and service clubs to request opportunities to speak about WBL at one of their meetings. Be sure to collect contact information for those in attendance and add it to the WBL database.

- Develop contacts and share information about WBL with economic development agencies, postsecondary institutions, workforce development boards, community-based organizations, non-profits such as United Way, and state departments of labor or commerce.

- Send information about WBL home to parents who, in addition to being advocates for their children’s education and career development, may be employers or employees who can participate in WBL activities.

- Tap into the personal networks of district and school staff to learn who can open which employer doors for the WBL coordinator.

- Contact local media outlets (print, radio, television, and school) to interest them in feature stories, appearances on talk shows, or coverage of WBL activities.

- Consider publishing a periodic electronic WBL newsletter with highlights of recent and upcoming WBL activities, including photos and quotes from participants. Include information on how to get involved in future WBL activities. The distribution list may include the full WBL database, but the frequency and length of the newsletter should be limited so that its arrival is welcomed.

It is worth remembering that WBL may not have been part of the high school experience of most adults in the community. The information you provide may be new to them and therefore especially interesting. In all of these awareness activities, the benefits of participation for students, school, and employers should be highlighted.

Targeted Recruitment of Employers for Work-Based Learning Participation

Outreach to employers to request participation in one or more WBL activities should usually be targeted to those that offer careers about which at least some students (and teachers) have expressed interest in learning. If approaching an employer that has never participated in WBL, it is a good idea to start with an activity that is easiest for the employer (e.g., guest speakers or workplace tours) and build on a favorable experience by later requesting a more challenging form of participation.

Each request should be tailored to the recipient, using information about the employer that has been researched and recorded in the database, and may offer a menu of choices of WBL activities. For example, asking a veterinarian with a solo practice to spend a whole day at a college and career fair, including preparing an exhibit, is probably not realistic, but asking them to speak to a class or host a job shadow might be more likely to elicit a favorable response. Similarly, recruiting employers in seasonal industries (e.g., agriculture, tourism, or construction trades) should focus on their off-peak seasons when they are more likely to be able to devote some time to a WBL activity.

Every request should include enough specific information to enable the recipient to determine if it is even feasible to consider a positive response. If a request is declined, the WBL coordinator should be prepared to offer an alternative WBL opportunity that better fits the employer’s schedule or ability to engage with students.

In the early stages of implementing WBL, it may be necessary to conduct research to identify what employers exist in the local area, what industries they represent, and how many employees they have. Local and regional chambers of commerce and other industry or trade associations can be helpful resources, as can service clubs, economic development agencies, workforce development boards, and state departments of labor or commerce. The WBL coordinator should not overlook public sector employers such as school systems, colleges and technology centers, and state and local agencies (e.g., emergency services, law enforcement, and human services). It may take a little more digging to identify small business owners and solo practitioners in occupations such as the building trades, design, health care, accounting, or the arts and to find ways to engage them in WBL activities that are not so time-consuming that they compromise their abilities to earn a living. This kind of research about employers might be an excellent school activity for a career readiness class, CTE class, state history and current affairs class, or another appropriate class. Students will acquire a great deal of career information by conducting this research and sharing their findings with classmates.

The WBL coordinator should make it a priority to identify and cultivate relationships with the largest local employers and those that offer careers in occupations of greatest interest to students. These are the “make-or-break” employers for the local WBL program.

The WBL coordinator should make it a priority to identify and cultivate relationships with the largest local employers and those that offer careers in occupations of greatest interest to students. These are the “make-or-break” employers for the local WBL program. The coordinator should identify the right contact within each organization (perhaps in human resources) and request an opportunity to acquaint him/her with the full range of WBL activities to determine which provide the right fit between student interests and the employer’s ability to accommodate them. Ideally, the employer and the coordinator could agree on a plan for participation in a variety of WBL activities at different times of the year. Such a plan would enable the coordinator to make specific requests in the context of an agreed-upon framework. Multiple, unconnected, and unexpected requests from multiple sources for WBL participation risk turning off the employer’s enthusiasm for WBL and conveying the impression that local WBL efforts are disorganized and inefficient. Instead, the WBL coordinator should use an “account management” approach and serve as a single point of contact for all communication with these high-priority employers (even if it is necessary to hand off some coordination responsibility for specific activities led by school-based staff). If managed effectively, these employers can become champions for WBL by helping recruit additional employers that are harder to reach. Over time, consistent use of the WBL database will facilitate an account management approach to coordination of WBL participation by every employer, which will, in turn, minimize intrusion into their routines and make it easier for them to say “yes” to WBL invitations.

Communicating with Employers

WBL coordinators will need to find a balance between the desire to keep employers informed and engaged in WBL and the risk of over-communicating and making employers feel like they are being bombarded by too many calls and emails that are not of specific value or interest to them. Following a few simple principles can help avoid this outcome:

- Coordinators should communicate only as frequently as necessary to get the job done.

- Clearly state the purpose of each communication, and its utility to the recipient.

- Use the least intrusive method that can accomplish the task (e.g., call vs. meeting, email vs. call).

Like most people, employers are busy and appreciate it when others show respect for their time. For communications about specific WBL activities, the coordinator should be prepared for every call or meeting, having researched the company and its prior WBL experiences and prepared a list of all topics to be covered. WBL coordinators should be clear about what is requested and when, why it is important, how students and the employer will benefit, and how and when the WBL coordinator will be in touch as implementation unfolds. Making sure the employer understands and accepts the responsibilities involved in participating in a specific WBL activity is the best way to avoid unpleasant surprises and ensure that implementation goes smoothly.

Employer Retention

Every business knows that it is easier and less costly to generate repeat business from existing customers than it is to acquire new ones. The same is true for employer participation in WBL programs. Employers whose initial experience with WBL is positive are much more likely to participate again, participate in the more challenging WBL activities, and to recruit their peers in their own organizations and others to participate in WBL. Key factors in employer retention include:

- Communicating clearly and concisely before, during, and after the activity.

- Ensuring that employers’ expectations for how the WBL activity will be implemented are met (i.e., no surprises.)

- Making certain that students are well-prepared to make the experience a positive one for the employer.

- Soliciting feedback that can be used to improve future WBL activities.

- Providing appropriate feedback, appreciation, and recognition.

In larger communities, an annual recognition event for all the employers who have taken part in WBL may be feasible. Other means of recognition may be more appropriate in rural areas. Over time, the WBL coordinator should check in at least annually with the employers that have been most active in WBL to ask for their thoughts on the strengths and weaknesses of the local WBL programs and learn whether they have had continuing contact with students they met through WBL participation (e.g., summer jobs, part-time work, or full-time employment after postsecondary education). Learning about some success stories can be very helpful in recruiting additional employers to participate in WBL activities. Conversely, learning from employers about any negative experiences can help in identifying changes that may be needed to ensure that future WBL activities lead to more positive experiences.

Resources

The most important resource for managing all the moving parts of a comprehensive WBL plan is the WBL database described earlier. A sample Excel template is provided here, but the design can be adapted to local needs, resources, and preferences. The WBL database may range from a simple spreadsheet to a more sophisticated information management database. The more schools and employers there are to track, the more an investment in the time it takes to set up a WBL database, using readily available software, will pay off in the long run. With a comprehensive WBL database, the WBL coordinator can generate reports on WBL contacts and participation at a specific school or employer or a list of WBL activities planned for the coming month, for example.

Copyright © 2020 CareerTech