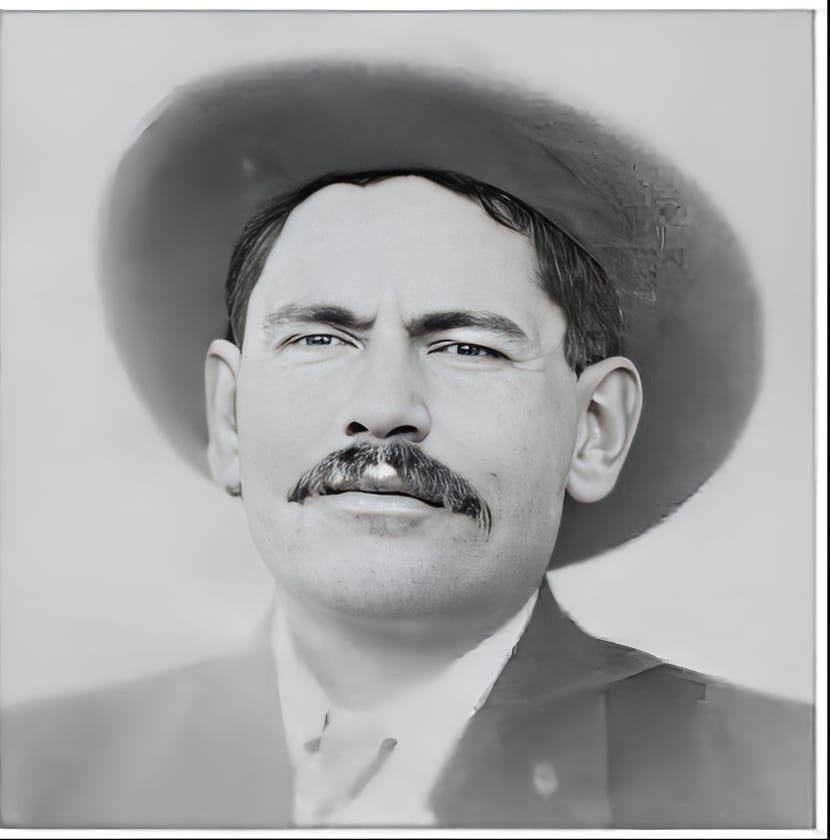

Deputy Warden

Oklahoma State Penitentiary

End of Watch - January 19, 1914

About the Agency

- Commissioners

- Directors

- Historical Timeline

- Memoriam

1890

The Legislature of the Oklahoma Territory authorized the Governor to contract with the State of Kansas for the incarceration and care of Oklahoma’s convicted criminals. The contracts were signed by the Territorial Governor and the warden of the Kansas Penitentiary and provided for the incarceration of Oklahoma’s criminal inmates who had been sentenced to incarceration for one year or more. For 25 cents per day, per inmate, Kansas provided "food, clothing, bedding, and medical treatment" for the inmates. This contractual arrangement served the needs of Oklahoma during its territorial days. There were numerous attempts by the Territorial Council to get a penitentiary bill passed, but the various governors never signed them into law.

1899

Rising costs and rising populations forced some Oklahoma officials to question the viability of continuing the contracts with Kansas for the incarceration of inmates. An 1899 report to the Governor indicated that the inmate population had reached a new high of 179 for the previous quarter. This growth, plus the increased rate per inmate, resulted in suggesting that the territory’s prisoners be cared for within the territory and that transportation costs be paid by the county where the conviction occurred. This suggestion never materialized.

1907

Charles N. Haskell

First Governor of the State of Oklahoma

(1907-1911)

Four months into his administration, the first Governor of the state of Oklahoma, Charles N. Haskell (1907-1911), recommended that the legislature appropriate funds to build a penitentiary and reform school in the new state. The legislature did not respond and three weeks before the first session recessed for the summer he sent a special message to both houses. He argued that the convicts were a large expense to the state without producing the slightest material benefit. Convicts could be used to work on the much needed public roads which "need not and should not compete with free labor." Again the legislature failed to act on the penitentiary bill.

Four months into his administration, the first Governor of the state of Oklahoma, Charles N. Haskell (1907-1911), recommended that the legislature appropriate funds to build a penitentiary and reform school in the new state. The legislature did not respond and three weeks before the first session recessed for the summer he sent a special message to both houses. He argued that the convicts were a large expense to the state without producing the slightest material benefit. Convicts could be used to work on the much-needed public roads which "need not and should not compete with free labor." Again the legislature failed to act on the penitentiary bill.

By the end of the first session, the legislature finally authorized the Board of Prison Control to purchase land at McAlester, Oklahoma, and to begin construction of a penitentiary using prison labor. The first contingent of 100 inmates from Lansing arrived on October 14, 1908, and the state temporarily housed this group at the former federal jail at McAlester. Under the direction of the new warden, Robert W. Dick, the inmates built a temporary stockade to house themselves and a second group of inmates from Lansing who Dick planned to use in constructing the permanent penitentiary. The stockade cell house was a clapboard, two-story structure, which measured 30 feet wide by 132 feet long. But the legislature stalled in appropriating funds for the construction of the permanent institution.

Governor Haskell reminded the legislature in January, 1909, that the contract with Kansas was due to expire at the end of the month. Since the legislature had not appropriated the construction funds, and had not yet renewed the contract, he wanted to know what action they would take regarding the 155 inmates at McAlester, over 562 at Lansing, and another 150 in county jails throughout the state that were waiting for "directions as to where they will be transported and confined."

Kate Barnard - Oklahoma's First Commissioner of Charities and Corrections

Barnard had received numerous complaints about the treatment of inmates and the general conditions at the Kansas Penitentiary. Soon after she assumed her official duties she visited the penitentiary at Lansing, Kansas, in August of 1908. She arrived unannounced and, joining other sightseers, paid the normal admittance fee of 50 cents for a guided group tour of the prison and was shown the "showplaces of the institution." After the tour, she identified herself and requested that she be allowed to conduct a thorough inspection. The warden and Kansas Board of Prison Control challenged her authority to inspect their prison, but finally allowed her full access to the facility under the watchful eye of the warden. She completed her inspection and returned to Oklahoma to write her report. She made her report public in December 1908, and demanded a full investigation.

She charged the Kansas authorities with corruption, brutality, and graft in their operation of the prison. Food conditions were terrible, she said, with the prisoners being fed only one meal a day and lower rations than the penitentiaries in Wisconsin and at Leavenworth, Kansas. Kate documented in her report that Kansas contracted the men to private individuals for 50 cents a day and received an additional 40 cents a day from Oklahoma, but spent only 11 cents a day for food.

Kate found that from 1905 to 1908, 60 boys had been sent to the Lansing Penitentiary and many of these were under 16 years of age. This was a clear violation of the contract which stated that "no convict shall be less than 16 years of age." This condition not only gave clear legal and moral grounds for terminating the contract, it also provided Kate with ammunition in her later attempt to establish state industry schools for youngsters in trouble with the law.

Barnard recommended, to the Governor and the legislators of Oklahoma, that all inmates be transferred immediately from Lansing to the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas, until Oklahoma could build its own penitentiary.

Conditions at Lansing Cause Public Outcry

The report on the conditions at Lansing brought about a public outcry to bring the prisoners back to Oklahoma. The official report of the investigation of the Lansing Prison was released only a few days after Governor Haskell informed the legislature that the contract with Kansas was to expire within three weeks. The report shocked the legislature into action and it authorized the movement of Oklahoma’s prisoners to McAlester, Oklahoma. After years of infighting, lethargy, and purposeful delay in dealing with the question of convict needs, the legislature finally moved to rectify the situation at Lansing. The legislature appropriated an initial $850,000 to construct the penitentiary.

Oklahoma Corrections Act of 1967

Finally, January 10, 1967, brought the historic announcement from Governor Dewey F. Bartlett in his Legislative address, when he said:

"I have prepared for introduction, today, a bill creating a new Department of Corrections. This bill has been prepared after consultation with leaders of both Houses of the Legislature. It is a joint recommendation of your leadership and the administration. Briefly, this bill provides for the creation of a new State Corrections Department, consisting of a State Board of Corrections, and State Director of Corrections, and three divisions: A Division of Institutions, a Division of Probation and Parole, and a Division of Inspection. The Division of Inspection will perform duties of the present Charities and Corrections Department."

On May 8, 1967, the legislature passed the Oklahoma Corrections Act of 1967. House Bill 566 created the seven-member Board of Corrections, with one member from each of the state’s congressional districts and a seventh member appointed at large.

Oklahoma Charities and Corrections Commissioners

Catherine (Kate) Ann Barnard

1907 – 1915

Kate Barnard was Oklahoma's first Commissioner of Charities and Corrections. She was also the first woman elected to state office in Oklahoma history – and the nation – before women had the right to vote. She persuaded lawmakers to adopt laws governing compulsory education and child labor, and establishing the state's juvenile justice system.

Barnard is perhaps best known for discovering horrific treatment of Oklahoma prisoners in a Kansas prison where they were housed. That led to those inmates' return to Oklahoma, construction of the state's first prison (Oklahoma State Penitentiary), and the establishment of a three-tiered state prison system: a penitentiary, reformatory and boys' training school.

Her advocacy led to 30 new state laws addressing establishment of today's Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services, the Oklahoma Department of Human Services, and the Oklahoma Department of Corrections. The Oklahoma Department of Corrections proudly named one of three female prisons in her honor.

William D. Matthews

1915 – 1923

William Matthews was a veteran of the Confederate Army, a former teacher and Methodist preacher. He was Oklahoma's second Commissioner of Charities and Corrections from 1915 - 1923.

However, when Matthews was elected, then-Gov. Robert Lee Williams appointed him to the state pension board, of which he became chairman. Consequently, most of his time over the state prison system was devoted to his duties with the pension board.

Mabel Luella Bourne Bassett

1923 – 1947

Mabel Bassett was Oklahoma's third Charities and Corrections Commissioner. She was elected for six consecutive four-year terms. Bassett believed the state needed to drastically reform its prison system, improve prison conditions, expand probation services, outlaw inhumane treatment and build a women's prison in McAlester, which now sits empty.

Bassett spent her 24 years in office fighting for what she believed was right, investigating neglect reports in every state orphanage, jail, prison or similar institution. She was a vociferous advocate, arguing mere incarceration would not protect society – only inmate rehabilitation would.

Bassett worked to establish and maintain standards for correctional facilities and state mental institutions. She also established the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board in 1944.

For her outstanding contribution to the state, she was inducted into Oklahoma's “Hall of Fame” by the Oklahoma Memorial Association on Statehood Day in 1937.

The Oklahoma Department of Corrections proudly named one of three female prisons in her honor.

Buck Cook

1947 – 1967

Buck Cook, who defeated Mabel Bassett in a 1946 runoff election, was Oklahoma's fourth Commissioner of Charities and Corrections. Under his administration, his office's duties were limited to routine inspections of jails and other institutions.

A former state trooper, he retired after holding the office for 20 years. That same year, the legislature enacted the Oklahoma Corrections Act of 1967, creating a new state agency to administer court-imposed prison sentences.

Jim Cook

1967 – 1977

The State Legislature enacted the Oklahoma Corrections Act of 1967 four months after Jim Cook took office as the fifth Commissioner of Charities and Corrections.

The act created a new Department of Corrections as of July 1, 1967. From 1967-1977, the Department of Corrections had both a Commissioner and a Director.

Cook resigned in 1977 after Oklahoma voters approved a constitutional amendment abolishing the position in 1975. The amendment did not take effect until January 1979.

Jack Stamper

1977 – 1979

An appointee of former Oklahoma Gov. David Boren, Jack Stamper led the Oklahoma Department of Charities and Corrections from October 1977 until the post ended in January 1979. He succeeded Jim Cook of Latimer County, who resigned after Oklahoma voters approved a constitutional amendment abolishing the position.

Before his appointment, Stamper served on the Oklahoma Wildlife Conservation Commission. He resigned that position to accept Boren's appointment.

Stamper was the former owner of the Hugo Daily News, the McCurtain County Gazette, which he bought in 1968, and former co-owner of the Antlers American, his obituary in The Oklahoman states. Stamper was also a veteran who served his country as a U.S. Army intelligence officer in Europe during World War II.

Directors

- Robert William Sumner

- Stephen Roshawn Jenkins, Sr.

- Rance McKee

- Jeff McCoy

- Joe Allen Gamble, Jr.

- Gay Carter

- Kenneth Denton

- Eugene Young

- Rex J. Thompson

- Raymond L. Chandler

- Albert J. Cox

- W. H. Aston

- W. H. "Pat" Riley

- William R. Benningfield

- Jess Dunn

- Charles D. Powell

- William C. Turner

- James Payton "Pate" Jones

- Charles Francis Christian

- William R. Mayfield

- D.C. "Pat" Oates

- Fred C. Godfrey

- Herman H. Drover

Robert William Sumner

Correctional Officer

John Lilley Correctional Center

End of Watch - July 14, 2024

Early morning on July 14, 2024, Corporal Robert Sumner was driving an ODOC van on his way to OU Medical Center in Edmond to work a hospital shift when he was involved in a traffic collision with another vehicle. Unfortunately, he passed away from his injuries at the scene. The other vehicle involved was JLCC Corporal Andrew Freppon, who was on his way to the facility to report for duty in his personal vehicle. Cpl. Freppon sustained serious injuries and was medi-flighted to a hospital. Cpl. Sumner and Cpl. Freppon graduated from the ODOC Academy in November 2023.

Corporal Sumner had served with the Oklahoma Department of Corrections for 11 months. He is survived by his wife and two children.

Stephen Roshawn Jenkins, Sr.

Correctional Officer

Clara Waters Community Corrections Center

End of Watch January 7, 2017

Corporal Stephen Jenkins suffered a fatal heart attack shortly after chasing an inmate across the prison yard at the Clara Waters Community Corrections Center in Oklahoma City.

The inmate was observed picking up a bag of contraband tobacco along the inner fence line at the prison. The inmate ran from Corporal Jenkins and three other officers when they attempted to take him inside for a disciplinary action. All four officers chased him across the prison yard before subduing him. Corporal Jenkins suddenly collapsed as they walked into the prison. Corporal Jenkins was transported to a nearby hospital where he passed away.

The inmate was charged with first-degree manslaughter as a result of Corporal Jenkins’ death.

Corporal Jenkins had served with the Oklahoma Department of Corrections for 18 months. He is survived by his four children.

Rance Lee McKee

Construction/Maintenance Administrator

James Crabtree Correctional Center

End of Watch - December 27, 2016

On December 27, 2016, at approximately 9:45 p.m., an officer noticed a smoky haze in the JCCC Unit 4 office area and detected a faint ozone odor, similar to an overheating electrical appliance. He searched the office and noticed a stronger odor in the attic and in a case manager’s office. He placed the unit on a 30-minute fire watch and requested that Central Control notify the chief of security. He also contacted the on-duty maintenance staff, Construction/Maintenance Administrator Rance McKee, to notify him of the issue. McKee stated that he would respond immediately to the facility.

McKee was struck by a vehicle after it failed to yield to a stop sign at an intersection. He was killed in the accident. The chief of security and the warden were called to the scene by the Oklahoma Highway Patrol, who investigated the accident. The OHP investigation determined the other driver was at fault for the collision.

Rance had served with the Oklahoma Department of Corrections for 27 years. He is survived by his wife and one son.

Jeffery Matthew "Jeff" McCoy

Probation and Parole Officer

End of Watch - May 18, 2012

On May 18, 2012, Officer Jeffery McCoy, 32, was shot and killed while performing a field visit at a home in Midwest City, Oklahoma.

Another man who lived at the home but was not the focus of Officer McCoy's visit answered the door and immediately pushed Officer McCoy off the front porch. The man then attacked him and was able to gain control of his service weapon during the ensuing struggle. He shot Officer McCoy at least once before fleeing back into his home and fired at officers from the Midwest City Police Department as they arrived at the scene. He was taken into custody moments later after he exited the home again.

Officer McCoy served with the Oklahoma Department of Corrections for seven years. He is survived by his wife and two children.

Joe Allen Gamble, Jr.

Correctional Officer

Oklahoma State Reformatory

End of Watch - June 5, 2000

On June 5, 2000, Sergeant Joe Allen Gamble was assigned to D Unit at the Oklahoma State Reformatory. At 8:15 a.m., Sergeant Gamble heard the call for help from Officer William Callaway. Sergeant Gamble immediately left the area he was counting and went through the unit control room to D-1 pod. When he arrived at D-1 pod, he did not know Officer Callaway had escaped the day room. Thinking only of his friend's call for help and without regard for his own personal safety, Sergeant Joe Allen Gamble entered the day room to save his fellow correctional officer. An inmate armed with two homemade knives ambushed Sergeant Gamble as he entered the day room. Sergeant Gamble was able to escape and ran immediately to medical for treatment. Sergeant Gamble was taken by ambulance to Jackson County Memorial Hospital where he later died from his injuries.

Sergeant Gamble had been with the department for three years.

Gay Carter

Correctional Food Supervisor

R.B. "Dick" Connor Correctional Center

End of Watch - November 13, 1998

Inmate John Grant stabbed Ms. Carter in the upper body several times with a homemade knife. Ms. Carter was supervising the cleaning of the dining hall after breakfast. Inmate Grant attacked her in the mop closet of the dining hall. He was convicted and sentenced to death on May 8, 2000, and was executed on Oct. 28, 2021, for her murder.

Kenneth Lee Denton

Correctional Officer

Oklahoma State Reformatory

End of Watch - August 3, 1989

At about 9:30 a.m., Officer Denton was transporting five inmate road workers in a Department of Corrections van. On Highway 9, about six miles east of Granite, Officer Denton suffered a heart attack while driving, causing him to lose control of the vehicle, which struck a bridge abutment and turned over. Officer Denton was pronounced dead at the scene and five inmates received minor injuries.

Denton served the agency for 19 years and was survived by his wife and two daughters.

Eugene Lee Young

Probation and Parole Officer

End of Watch - July 28, 1989

On the afternoon of July 28, 1989, at the Oklahoma City probation and parole office, parolee Huey Don Turner was being arrested during his visit to the office preparatory to have his parole revoked. Turner resisted violently, and Officer Young was one of five corrections officers called to subdue him. A short time later, Officer Young suffered a heart attack and died at Presbyterian Hospital in Oklahoma City.

Officer Young was survived by his wife, two sons and two daughters.

Rex James Thompson

Correctional Officer

Lexington Corrections Center

End of Watch - September 1, 1981

On August 31, 1981, at about 7 p.m., the prison's officers were in the process of locking all of the inmates in their cells as part of a general lockdown because of a previous fight. Inmate Michael Slazenger attacked Officer Thompson near his station in the control center. Officer Thompson died from severe head injuries the next day.

Officer Thompson served the Oklahoma Department of Corrections for three years and was survived by his wife and two children.

Raymond L. Chandler

Correctional Officer

ODOC Security - Griffin Memorial Hospital Unit

End of Watch - December 18, 1980

Officer Chandler was off duty at a laundry mat in Norman when a former inmate walked in, and a fight ensued. As the two struggled, both fell through a large plate glass window. A large piece of glass cut Officer Chandler’s jugular vein as he fell. After falling through the window, the semi-conscious officer, dressed in street clothes, fired one shot from a handgun at the offender who was running away, but he did not strike the ex-inmate. Chandler then collapsed and died at the scene.

At the time of his death, Officer Chandler was assigned to the inmate unit at Griffin Memorial Hospital.

Albert Jerald "Abe" Cox

Prison Farm Supervisor

Oklahoma State Penitentiary

End of Watch - March 5, 1977

At 9:30 a.m., on March 5, 1977, inmate trustee Edward Lyle Hall and employee Albert Cox were discovered missing from the state prison. At 5 p.m., Mr. Cox's body was found under more than two dozen 50-pound sacks of feed in a chicken coop in the prison farm. He had been stabbed several times and his throat had been slashed by a homemade knife. Hall took Cox's prison work truck. It was located abandoned 80 miles away in Johnston County.

Later that day, near Mannsville, the suspect held a knife to the throat of an 11-year-old boy and forced him and his father to drive him to a remote location before releasing them unharmed and taking their vehicle. Five days later, the car was found abandoned in Florida. On October 4, 1977, the suspect was captured by FBI agents in Denver, Colorado.

Hall, who was serving a 15-year sentence for a 1974 robbery conviction, was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death. In 1982, his conviction was overturned and a new trial was ordered. He was found guilty of second-degree murder and sentenced to life. Hall was denied parole several times and died in 2024.

Cox had served with the Oklahoma Department of Corrections for 12 years. He is survived by his wife and two children.

William Henry "W.H." Aston

Officer

Oklahoma State Penitentiary

End of Watch - August 4, 1948

On July 30, 1948, Officer W.H. Aston was on duty on the fourth floor of the west cellblock, the solitary confinement area. Officer Aston saw a mirror, prohibited in solitary confinement, extended from Thomas Woods' cell and went to check on it. When he opened the cell door, Woods sprang upon him and began beating Aston's head on the floor, wall and against the cell bars.

When other officers came to his rescue, Aston was still conscious, and his injuries did not appear serious. He was taken to a local hospital but did not want to be admitted. He was examined and sent home, but the next day, his condition worsened. Taken to a hospital in Holdenville, he was diagnosed as suffering from a fractured skull and intracranial bleeding. Officer Aston died of his injuries on August 4.

W. H. "Pat" Riley

Chief Sergeant

Oklahoma State Reformatory

End of Watch - December 13, 1943

On December 13, 1943, prisoner L. C. Smalley told Chief Sergeant W. H. “Pat” Riley that he had been robbed of a watch and $30 by two other prisoners. Smalley told Riley that the men who robbed him were Mose Johnson and Staley Steen. At about 3:15 p.m., Sergeant Riley located both suspects in the boiler room where they worked. As he questioned them about the robbery, Johnson hit Riley over the head with a piece of pipe, and Steen stabbed him in the face and back with a knife. Leaving the officer on the floor, the two inmates ran to the canteen, where Smalley worked behind the counter. When the two ran into the canteen, the other inmates ran out before Johnson killed Smalley with an ice pick. Other officers arrested the two in the canteen but not in time to save Smalley.

Sergeant Riley had been with the agency for ten years and was survived by his wife, a daughter and four sons.

William (Wolford) Rufus Benningfield

Supervisor

State Prison Farm

End of Watch - August 11, 1941

James David Parrish, a trusty serving time for Grand Larceny, complained of feeling ill. Mr. Benningfield, an unarmed supervisor, was transporting him to the doctor in Atoka, but they never arrived. The car was found abandoned near Wewoka, with its gears stripped. Parrish was arrested that night while hitchhiking near Shawnee, Oklahoma, on Highway 270. Confessing to Benningfield's murder, he led officers to the body in a ditch 14 miles north of Durant. Benningfield had been beaten to death with a claw hammer.

Jess Fulton Dunn Sr.

Warden

Oklahoma State Penitentiary

End of Watch - August 10, 1941

On the morning of August 10, 1941, Warden Dunn was touring the prison with an electrical engineer, planning a new communications system. At about 10:45 a.m., prisoners Roy McGee, Bill Anderson, Claude Beaver, and Hiram Prather, armed with homemade knives, tried to break out of the prison. Anderson and Beaver had both been involved in a previous escape attempt that cost the life of Charles Powell four years earlier.

The inmates took Warden Dunn and the engineer hostage and began marching them out in the yard, using them as shields from the officers. Threatening to kill their hostages, the prisoners managed to disarm the officers in the front guard tower. Now armed with guns, they forced their hostages out to the front gate. In the meantime, officers had called the Pittsburg County Sheriff's Office for assistance. Deputy Sheriff Bill Alexander was the only officer on duty, but Deputy William A. Ford was also at the Sheriff's Office, although he was off duty. Both deputies had formerly been officers at the prison.

The deputies quickly drove to the prison and, using their car as a roadblock, about three blocks north of the prison, blocked the exit of the car containing the inmates and hostages. During his time as an officer at the prison, Deputy Alexander had discussed with Warden Dunn how an attempted jailbreak should be handled if hostages were involved. Dunn had told Alexander that if prisoners took him hostage, they would have him order the officers to let them pass and not to shoot. Also, obviously, he would give the orders as they told him. However, Dunn told Alexander that the officers should ignore his orders under those circumstances and not let them pass. He also told him that "even if I tell you not to shoot, you shoot."

Claude Beaver was driving with Warden Dunn and the engineer in the front seat of the car, with the other three escapees in the rear seat holding them at gunpoint. As expected, the prisoners told Dunn to give the deputies the orders to let them pass. Deputy Alexander told the Warden he could pass but that the other men would not be allowed to leave. One of the prisoners then fired a rifle shot, hitting Deputy Ford in the head. Another prisoner then shot Warden Dunn twice in the back of the head, and Deputy Alexander began returning their fire.

Warden Dunn, Roy McGee and Claude Beaver were dead at the scene. Deputy Ford died a few hours later. Bill Anderson died from his wounds two days later. Hiram Prather, also wounded, was the only one of the prisoners to survive. He was charged with Jess Dunn's murder, convicted, and sentenced to die in "Old Sparky," the prison's electric chair. The engineer was found in the car's floorboard, uninjured.

Jess Dunn was the warden at OSP from 1934-1941 and was survived by his wife and two adult sons.

Charles D. Powell

Brickyard Foreman

Oklahoma State Penitentiary

End of Watch - May 13, 1936

About noon on May 13, 1936, the prisoners were being fed lunch in the brickyard when a jailbreak occurred. Twenty-four men charged four officers, including Mr. Powell, with prison-made dirks. Powell attempted to escape from them but was struck on the head with a piece of pipe. The four hostage officers – Powell, Tuck Cope, W.W. Gossett and Victor Conn – were then forced toward the nearest guard tower. When the prisoners demanded that the two tower officers throw down their guns, the officers complied.

The now-armed inmates forced their captives to a nearby car, and 14 of the escapees crammed themselves into and on the car. As the car began moving, other officers opened fire on the car. Cope was wounded in the neck, Gossett in the stomach, but Powell was fatally hit in the head. In the resulting melee, 10 of the inmates were wounded and six were rapidly recaptured. Eight escaped for a few hours to several weeks, but all were subsequently recaptured.

Officer Powell had been with the agency for five years and was survived by his wife and two children.

William Clifford “Bill” Turner

Guard Foreman

Oklahoma State Penitentiary

End of Watch - July 18, 1935

On July 18, 1935, Guard Foreman Turner was supervising three prisoners on the prison farm about a mile from the main prison building. He was suddenly struck by lightning, killing him and the horse he was riding. The three prisoners who were stunned and burned also by the lightning bolt carried Turner’s body back to the prison. No prisoner escaped. They were all hospitalized but were not seriously hurt.

Turner served as an Atoka County Deputy Sheriff before joining the staff of the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in 1931 and soon became a foreman of guards. He was survived by his wife and three children.

James Payton "Pate" Jones

Security Officer

Oklahoma State Reformatory

End of Watch February 17, 1935

On February 17, 1935, Officer Jones was on duty in the main entrance tower. Shortly after 2 p.m., two inmates, Malloy Kuykendall and Henry Stewart, led a mass escape (32 inmates total) attempt with two guns that had been smuggled into them.

Unfortunately, a group of women and children were taking a tour of the prison at the same time and the prisoners took them hostage. As the group approached the main tower where Officer Jones was on duty, one of the inmates shot him fatally with a shotgun. Officer Jones' wife was standing on the front porch of the officers' barracks a short distance away and saw her husband shot down.

Officer Jones had been with the agency for three years. He was survived by his wife and two children.

Charles Francis Christian

Correctional Officer

Oklahoma State Reformatory

End of Watch - February 16, 1935

On February 16, 1935, Correctional Officer Charles Francis Christian was the victim of an attack by an inmate while he was supervising a work gang at the Oklahoma State Reformatory. Officer Christian never recovered and succumbed to his injuries from a crushed skull.

Charles Christian, a widower, was survived by three children.

William Robert Mayfield

Brickyard Supervisor

Oklahoma State Penitentiary

End of Watch - January 20, 1926

On January 19, 1926, William Mayfield was the supervisor for the brickyard at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester. One of the prisoners in the brickyard that day was originally sentenced to five years for burglary, but in 1925, the inmate had killed his cellmate and received an additional twenty-five-year sentence. This inmate had a plan to escape on this date.

To escape, the inmate threw a brick at Mayfield, striking him in the back of the head, which caused a deep wound and a fractured skull. Other officers then shot the inmate. Mayfield succumbed to his injuries and died the next morning.

He was survived by his wife and four children.

At 4:20 p.m., January 19, 1914, three prisoners (Tom Lane, Chiney Reed and Charles Kuntz) were making their way through the maximum-security prison's front corridor, ostensibly to see parole officer Frank Rice. Tom Lane was concealing a handgun that had been smuggled into the prison for him.

As Turnkey J. W. Martin let the inmates through the door, Lane pulled the gun on him and demanded the keys. Martin, alone and unarmed, jumped Lane and struggled with him until Lane shot him in the cheek. The inmates then took the keys and ran down the corridor to the office of Deputy Warden Pat Oates, intending to take a hostage to help protect their escape from the armed officers in the towers outside.

Turnkey Martin raised the alarm, and Deputy Warden Oates came out of his office, drew his handgun, and emptied it at the inmates, wounding Kuntz in the chest. Tom Lane returned fire. Herman Drover was exiting another room from developing photographs and was fatally hit by one of Lane's shots. Oates ran down the hall to get another gun or more ammunition.

As the inmates burst into the deputy warden's office, they confronted stenographer Mary Foster, day sergeant F. C. Godfrey, parole officer Frank Rice, and attorney John H. Thomas, who was at the prison to see a client. As the inmates told everyone to raise their hands, the elderly Thomas moved too slow to suit them, and Lane shot him fatally. Sergeant Godfrey, who was facing a wall with his hands raised, then attacked Lane, who shot him in the head, killing him instantly. The inmates then took Foster and Rice as hostages and, shielding themselves behind their hostages, moved out of the office. Deputy Warden Oates, who had rearmed himself with a shotgun, met them in the corridor. Oates ordered Lane to drop his gun, and Lane shot Oates, killing him. Subsequently, all three inmates were killed during the escape attempt.

Pat Oates served three years as a deputy sheriff and four years as Sheriff in Woods County before being appointed as deputy warden of the State Penitentiary in 1909. He was survived by his wife and two children.

Fred Godfrey was survived by his wife and son.

Herman Drover was survived by his wife and two adult sons.